Newsletter

Are Your Processes Innovative or Merely Electronic? Leverage Technology the Right Way

Decades of innovation have transformed the finance office from a mindset of processing transactions to one of strategic financial management. But even with this advancement, nonprofit organizations are operating in an increasingly complex environment that requires them to balance routine and new tasks with a higher volume of information.

When the topic of efficiency is raised to an organization whose finance team is at capacity, it is not unusual to hear the team is already using technology and that, perhaps, no further innovation is possible. However, asking a few questions helps to uncover whether the tools they have implemented are really transforming their processes or whether they have merely replaced manual processes with electronic ones.

Confusing “Electronic” With “Innovative”

As a result of the pandemic, most finance offices were forced to shift to virtual operations. Understandably, many were unable to put a strategic plan in place before making this transition and simply replicated a manual workflow that layered into it an electronic component, such as email or another paperless option. Many of these workflows still exist today but present confusing workarounds for typical tasks, such as:

- Emailing vendor invoices as message attachments, with approval indicated in the body of the email message, and then saving the email as a PDF as supporting documentation and manually entering data from the invoice for payment processing.

- Completing time sheets via spreadsheets that then are manually reviewed, corrected and compiled for manual data entry into the payroll system for processing.

- Using shared electronic folders for collecting scanned credit card receipts for manual reconciliation via spreadsheet at month’s end.

What all these examples have in common is that they replace paper with an electronic file. But these modifications do not introduce any real workflow changes or innovative technology that is designed and customized to support that workflow. In fact, workflows like this can be less efficient and less effective, especially in a high-volume environment.

Real Innovation

There are a variety of innovative technology solutions that enhance efficiency and effectiveness for the finance team. For example, the following simple solutions can help address the situations above:

- Utilize one of the many electronic accounts payable (AP) tools that enable electronic invoice routing based on an organization’s defined approval workflow, facilitate electronic coding that syncs to the general ledger and have a mobile app option. These tools also will facilitate electronic vendor payments without time-consuming manual data entry.

- Implement electronic time sheets that work with your organization’s payroll processing technology, eliminating the potential for mathematical errors, facilitating tracking paid time off and syncing for payroll processing without manual entry.

- Consider an expense management system with mobile app capability. Similar to the AP solutions, these tools allow credit card holders to take pictures of receipts and other supporting documentation, code and approve within the app, and facilitate month-end reconciliation. Expense management systems are also designed to automate employee expense reimbursements in a similar way.

Beyond electronic accounts payable, time sheets and credit card management, other common areas for innovation include:

- Automated financial reporting—including budget versus actual, dashboards and forecasting—that reduces the need to download data to a spreadsheet for manual report creation.

- System integrations, so that information—including development revenue, inventory balances or deposit details—is automatically updated in the general ledger and not manually entered.

- Expense allocations that are automatically calculated based on set parameters to avoid time-consuming calculations.

- Document routing and storage systems that are designed to circulate important items—including grant agreements, information for grant reports and vendor contracts—for internal approval and to house final versions in a central location.

When beginning to assess which tools may improve efficiency, it is helpful to focus first on the most time-consuming areas for the finance team, also keeping in mind how the team would spend time if capacity were increased. These are just a few of the most common areas for innovation, and there is certainly no shortage of technology solutions. BDO can help organizations assess finance team infrastructure needs, including opportunities for technology innovations, and help with related implementation and internal training.

© 2023 BDO USA, LLP. All rights reserved. www.bdo.com

Form 990 Review: What Nonprofit Boards Should Look For

Many in the nonprofit world know Form 990 as the all important nonprofit tax form that details an organization’s activities and financial standing. In addition to justifying an organization’s tax-exempt status, Form 990 reveals key information that charity-rating organizations and grantmakers use when evaluating nonprofits.

The IRS does not mandate that nonprofit boards review Form 990, but due to the form’s importance, board review is a widely adopted best practice. And if the board does review the form, the IRS requires an organization to disclose its Form 990 review process. Establishing a consistent board review process helps organizations mitigate compliance risk, but also helps board members identify and address any issues that may raise a red flag to funders, donors and charity watchdogs.

Form 990 should include detailed information about the significant programs the organization conducts, how much revenue it generates and where it is spending money. It’s also important to note that prominent foundations and other philanthropic institutions look for a detailed Form 990 during their grantmaking due diligence, and making sure this information is accurate, up-to-date, and readily available can help board members secure larger donations.

Enhancing Accuracy and Addressing Compliance Concerns

Most nonprofit boards see reviewing Form 990 as a part of their fiduciary responsibility to the organizations they serve. Given this responsibility, legal and financial professionals who have the skills to understand the information reported in the return and flag compliance concerns can provide a great deal of value as nonprofit board members. When reviewing Form 990, here are some issues the board should look for:

- Compensation issues: If the IRS determines nonprofit executives are unreasonably compensated, executives may be liable to pay an excise tax and return the excess benefit. Board members who approve the excessive compensation may also be liable for an excise tax. Beyond the IRS, funders and donors may also want to understand how executive compensation is determined as they make funding decisions.

- Cost allocation: In part IX of Form 990, nonprofits are required to allocate their expenses between program service activities, management and general expenses, and fundraising. The IRS requires that the process for cost allocation is reasonable under the circumstances and that the allocation process is documented thoroughly. Additionally, charity watchdogs and funders and donors will analyze what percentage of overall funding is going toward program activities to help determine their funding decisions.

- Transaction and loan ethics: The IRS is interested in transactions that may involve “interested persons” such as directors and officers and others with substantial influence in the organization. These transactions are disclosed in Schedule L of the return and should be “at fair market value and arm’s length” as it pertains to the nonprofit. Board members should review Form 990 for these transactions in order to confirm that they meet the arm’s length and fair market value standard. In addition to transactions, loans made by an organization to an interested person could raise a red flag. The IRS will look for these loans to carry commercially reasonable terms and carry an interest rate and security as a bank loan would.

If organizations cannot demonstrate that transactions and loans “are at fair market value and arm’s length,” the organization and individuals involved could be subjected to excise tax penalties. If these transactions and loans are particularly egregious, they could jeopardize the organization’s tax-exempt status.

As nonprofits face increasing demands for transparency, a formalized board review process for Form 990 can help organizations put their best foot forward with the IRS, the public and donors.

Creating a Powerful Narrative to Support Your Mission

Form 990 is an important component of an organization’s ability to navigate increasing scrutiny and pursue funding opportunities. By applying their knowledge and experience to the reporting process, board members can help the nonprofits they serve maintain compliance with IRS regulations as well as reinforce the organization’s commitment to its mission in the eyes of donors and the public. Finally, a detailed Form 990 arms the organization with the information it needs to communicate its story, highlights the impact of its work, and makes a compelling case to donors, grantmakers and the public at large.

© 2023 BDO USA, LLP. All rights reserved. www.bdo.com

Cash Benefits for Supporting ESG – New Markets Tax Credit

With an increasing focus on environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues, some organizations are seeking ways to fund various ESG initiatives. Tax credits and incentives have played an important role in subsidizing ESG initiatives, with the Inflation Reduction Act significantly enhancing their impact on environmental investments. However, the often-overlooked social aspect of ESG can also be supported by tax credits and incentives.

The social dimension of ESG focuses on an organization’s relationship with society, including the well-being of employees and the communities the organizations operate in. One mechanism that organizations can utilize to fund initiatives supporting local communities is the New Markets Tax Credit (NMTC)

What is the NMTC?

The NMTC is a federal program established in 2000 to incentivize investment in low-income communities. Codified under Internal Revenue Code Section 45D, the program has been continuously extended through legislative packages. The latest extension provides a $5 billion annual allocation through 2025.

The CDFI Fund, an agency of the U.S. Treasury, administers the program through certified community development entities (CDEs). CDEs use the NMTC allocation to generate a 39% tax credit, which can be monetized by tax credit investors.

Using tax credit equity, the CDEs fund projects in low-income communities, often through loans with flexible features such as below-market interest rates and principal forgiveness.

CDEs help the CDFI Fund allocate funds nationwide, carefully selecting projects that have a significant impact on low-income communities. These projects commonly focus on creating jobs, developing the workforce, providing goods and services to the community, improving healthcare and other community benefits.

The NMTC program requires annual reporting of community outcomes generated by each project, making it an effective tool to support the “S” in ESG initiatives.

Nonprofits and the NMTC

Nonprofit organizations receive a significant portion of NMTC funding each year. The social mission of nonprofits aligns well with the NMTC program’s goal of community development, particularly for underserved populations. NMTC funds often serve as a valuable source of funding for nonprofits to supplement their capital campaigns and other fundraising efforts.

However, nonprofits face challenges in utilizing the leveraged structure commonly used for NMTC funding. In a leveraged structure, tax credit investors create an investment fund that combines their tax credit equity with other financing sources to provide project funding. One challenge nonprofit organizations face is that the leveraged structure typically requires two taxable entities. To address this, many nonprofits establish supporting organizations to facilitate NMTC transactions. Additionally, securing upfront funding sources can create time-value pressure on cash flow, especially for nonprofits that finance their projects over time.

To illustrate how NMTCs can support a project, consider a nonprofit health clinic that aims to expand its facility and acquire equipment to enhance services for disadvantaged individuals in an eligible low-income census tract. The total project cost is $10 million and, despite receiving donations and other funding sources, the clinic can raise only $7.5 million. The clinic can bridge the financing gap through an NMTC loan, which is funded by the tax equity generated from the CDE’s NMTC allocation, enabling the project to move forward. An additional advantage is that the NMTC loan principal is often forgiven after a seven-year term, resulting in a permanent cash benefit to the organization.

© 2023 BDO USA, LLP. All rights reserved. www.bdo.com

Nonprofits Pivot from Survival to Resilience: BDO 2023 Nonprofit Standards Benchmarking Survey

The BDO 2023 Nonprofit Standards Benchmarking Survey of more than 250 nonprofits highlights a crucial shift in the nonprofit sector towards strategic resilience, marking a departure from the reliance on recent federal funding. Data from our annual survey reveals that in response to economic uncertainties, nonprofits are prioritizing digital transformation (42%), cost reduction (38%), and seeking new funding sources (36%) as their top concerns for the next 12 months. Despite a decrease in revenue for 44% of surveyed nonprofits in the latest fiscal year, 69% anticipate an increase in the coming year.

The nonprofit industry has continually turned crisis into opportunity, and this year is no different. While less than half (44%) of surveyed nonprofits saw increased revenue in their most recent fiscal year, 69% anticipate revenue will increase in the next fiscal year. Nearly all (99%) surveyed organizations say they have expanded or shifted their mission scope in the past 12 months, with more than half doing so to address emerging needs among the populations they serve. Organizations are also focused on efficiency and strengthening bottom lines, identifying digital transformation, cost reduction and finding new revenue and funding sources as their highest priorities over the next 12 months.

Even in the face of economic uncertainty, nonprofits are showcasing their determination amid a decline in giving and higher costs. Investment in technology is a priority in the coming year. More than half (59%) of nonprofits plan to increase their technology spending in the next 12 months, and 57% plan to select and/or implement a new enterprise resource planning (ERP) system within the same time frame.

The report also delves into increased donor scrutiny surrounding ESG topics. Just over half (51%) of nonprofits say funders and donors have asked for more information on ESG strategy in the past 12 months, while 42% said they are seeing an increase in requests for information on environmental impact and reduction strategies.

Now in its seventh year, Nonprofit Standards examines emerging challenges and opportunities facing nonprofit leaders, offering data-backed insights they can use to further their missions and sustain their organizations into the future. The survey includes an overview of the nonprofit sector as well as breakout reports for health and human services organizations, higher education institutions, grantmakers and their recipients, public charities, international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs) and organizations with more than $75 million in revenue.

How does your organization compare to peers? Benchmark yourself.

© 2023 BDO USA, LLP. All rights reserved. www.bdo.com

Do You Know Who Is Watching?

The chorus of a popular ’80s song says, “I always feel like somebody’s watching me.” Not-for-profit entities (NFP) have their financial information available on a variety of platforms including, but not limited to, the NFP’s website, the public inspection copy of its Form 990, and perhaps on its state attorney general’s website, if the NFP solicits donations from the public. This public exposure of financial information might have NFPs feeling like somebody’s watching them, and they would be correct!

Potential and existing donors look at an NFP’s financials to understand how the entity is doing overall and how donations are spent on program services before committing to donate. Watchdog organizations also review and assess this information. A watchdog organization is typically a nonprofit group that monitors the activities of governments, industry or other organizations and alerts the public when actions that go against the public interest are detected. It is important that management and those charged with governance understand the watchdog organizations, the rating platforms and the methodologies behind those ratings. There are many of these organizations, but this article will focus on three prevalent organizations: Charity Navigator, Candid and the Better Business Bureau Wise Giving Alliance.

These three watchdog organizations have an enrollment process for nonprofits. Once the application is approved, the nonprofit may provide pertinent information that will be used by the watchdog organization to provide information to the public.

Charity Navigator

Charity Navigator’s mission is to make impactful giving easier for all by providing free access to data, tools and resources to guide philanthropic decision-making. Charity Navigator’s methodology involves ratings, curating lists and providing alerts.

Ratings

Charity Navigator focuses on two objectives in its approach to ratings: helping others and celebrating the work of charities. The types of charities assessed by this watchdog organization are 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organizations, which are U.S.-based organizations commonly referred to as public charities.

Eligible charities receive a zero- to four-star rating determined by the weighted sum of the organization’s individual beacon scores. Charity Navigator’s Encompass Rating SystemTM provides a comprehensive analysis of charity performance across four key domains, referred to as “beacons.” The beacons are as follows:

- Impact and Results – determines if a nonprofit is making good use of resources to address the issues it aims to solve.

- Accountability & Finance – evaluates a nonprofit’s accountability and transparency as well as its general financial health, and includes measures of stability, efficiency, and governance.

- Leadership & Adaptability – evaluates the nonprofit’s leadership practice and ability to respond to change.

- Culture & Community – evaluates the nonprofit’s overall culture and its connectedness to the constituents and community it serves.

Charity Navigator established this more encompassing rating system to fairly assess nonprofits across domains that influence organizational performance and success. By expanding the assessment beyond financial metrics, donors are provided with a more holistic understanding of nonprofit performance.

To be eligible for an overall rating, organizations must have an Impact & Results score and/or an Accountability & Finance score. Nonprofits that do not or are unable to earn an Impact & Results or Accountability & Finance score at the time of application can still earn scores for Culture & Community and Leadership & Adaptability. Charity Navigator’s rating system is not established to be all or nothing. It is designed to provide potential donors with as much meaningful information about the organization as is available.

The breakdown of the ratings is outlined below:

Rating Score Assessment Description

- 4 star, 90+, Great Exceeds or meets best practices and industry standards across almost all areas. Likely to be a highly-effective charity.

- 3 star, 75-89, Good Exceeds or meets best practices and industry standards across some areas.

- 2 star, 60-74, Needs improvement Meets or nearly meets industry standards in a few areas and underperforms most charities.

- 1 star, 50-59, Poor Fails to meet industry standards in most areas and underperforms almost all charities.

- 0 star, <50, Very poor Performs below industry standards and well underperforms nearly all charities.

Curated Lists

In order to help donors navigate their giving, Charity Navigator compiles lists of charities divided into three distinct categories:

- Where To Give Now – aims to respond to donors’ and media’s existing interest in certain trending topics. The charity needs to have a three or four-star rating, have clear and concentrated efforts responding to the issue as described on its website, and if facing a specific crisis, allows donors to designate their donations to the crisis-specific efforts.

- Popular Charities – highlights some curated groups of ratings and is often a popular area of interest for donors. These are the most searched for, visited, and supported on Charity Navigator.

- Best Charities – aims to highlight exciting giving opportunities that donors may not be aware exist. To be included, a charity needs to have a three- or four-star rating and has to run a particularly impactful program based on specific criteria.

Alerts

When a charity is reported to engage or confirmed to have engaged in misconduct or questionable practices, Charity Navigator posts an alert on the charity’s profile page to raise awareness and help inform donor’s giving. In issuing an alert, Charity Navigator’s Alert Issuance Committee considers the following:

- Credibility (based on a media outlet that Charity Navigator deems reliable) and timeliness of information

- Nature, scope, and seriousness of the allegations or convictions

- Whether or not the allegations have been proven

- Other factors on a case-by-case basis

Charity Navigator has the following four levels of alerts:

- Review Before Proceeding – this alert is given if matters of concern relating to the organization have been reported, but to Charity Navigator’s knowledge, no legal proceeding has commenced, or the matter is not of a legal nature.

- Proceed with Caution – this alert is given if a credible media outlet has reported that a government agency or a private third-party has filed charges or brought a claim as part of a pending legal proceeding, alleging that the organization or its managers have engaged in illegal conduct, including but not limited to financial wrongdoing, discrimination, or violation of data security laws.

- Proceed with Increased Caution – this alert is given if a credible media outlet has reported that the organization is engaged in bankruptcy proceedings or the organization has been found, through a legal proceeding, to have engaged, or have managers who have engaged, in illegal conduct including, but not limited, to financial wrongdoing, discrimination, or violation of data security laws.

- Giving Not Recommended – this alert is given if the organization lacks 501(c)(3) status or a credible media outlet has reported that the organization has engaged, or have managers who have engaged, in substantial fraud or misrepresentation relating to the organization’s charitable purposes or activities, as determined through a legal proceeding.

Candid

Candid, a nonprofit that provides comprehensive data and insights about the social sector, was formed with the 2019 merger of GuideStar and Foundation Center. GuideStar was a public charity that collected, organized and presented information about every IRS-registered nonprofit organization. The Foundation Center collected and communicated information on U.S. philanthropy, conducted research on trends in the field and provided education and training on the grant-seeking process. Candid continues to operate both of these arms.

Candid’s mission is to find where the money nonprofits spend comes from, where it goes and why it matters. To fulfill this mission, Candid works with nonprofits to identify funders who support the organization’s work by listing their information in its Foundation Directory. On the flip side, funders use GuideStar to verify and research nonprofits aligned with their focus.

- Foundation Directory

Candid’s Foundation Directory gives nonprofits access to information allowing them to be smart and strategic with funding requests. Nonprofits can choose from either the Essential plan or the Professional plan. The Foundation Directory allows nonprofits to enter a phrase for what it is looking for and, based on that phrase, a results page is produced that includes Grantmakers, Grants, and Recipients. Grantmaker profiles provide a powerful summary overview of the funder’s work along with all the pertinent details nonprofits need to find and approach great prospects. - Tools for Funders

Candid offers various tools funders can use to research the operations and financials of nonprofits. In order for this information to be available, nonprofits must have an account with Candid. Once the nonprofit’s profile is approved, the nonprofit can tell its story through its profile. The Candid platform is driven by each nonprofit and the information they decide to showcase. Using the profiles created by the nonprofits, Candid provides the following tools for funders:- GuideStar Pro – Funders use Candid’s nonprofit profiles for research, due diligence, and, increasingly, as part of the grant application process. Search for information on more than 1.8 million nonprofits, including mission, vision, values, programs, leadership, staff and board demographics, and finances.

- Charity Check– Validate nonprofits’ status and ensure compliance with Charity Check, which is compliant with all IRS requirements. Get alerts on nonprofit status changes and monitor organizations. Funders can quickly understand key elements of a nonprofit’s operations through Candid’s Seals of Transparency which is part of the Charity Check. The levels of seals are as follows:

- Bronze Seal – this is awarded to a nonprofit with a profile that includes its mission and contract details, donation information, and leadership information.

- Silver Seal – this is awarded to a nonprofit with a profile that includes the information at the bronze seal level and additional information regarding program information, grantmaker status and brand details (website, social media, logo).

- Gold Seal – this is awarded to a nonprofit with a profile that includes the information at the silver seal level and its audited financial report or basic financial information, and its Board Chair names along with leadership demographics.

- Platinum Seal – this is awarded to a nonprofit with a profile that includes the information at the gold seal level and includes its strategic plan or strategy and goal highlights, and at least one metric demonstrating its progress and results.

- Data Integration and Partnerships – Candid provides comprehensive social sector data through its Application Programming Interfaces and custom data services. Candid also partners directly with organizations that share value of transparency.

- Improve Your Community Foundation’s Performance – Council on Foundations Insights helps members assess and improve their community foundation’s organizational performance through peer benchmarking. Candid also creates connections to others in the field who are interested in sharing knowledge and increasing impact.

For more information, please visit Candid

Better Business Bureau Wise Giving Alliance

The Better Business Bureau (BBB) Wise Giving Alliance (WGA) is a standards-based charity evaluator that seeks to verify the trustworthiness of charities publicly soliciting donations. The BBB WGA helps charities build trust and donors give wisely.

The BBB WGA’s foundation is the BBB Charity Standards, 20 standards addressing four themes. Following are the four themes and an overview of each theme and its corresponding standards. For each of the 20 standards noted below, the BBB WGA assigns a finding of (1) standard is met, (2) standard is not met, or (3) unable to verify.

- Governance and Oversight – The governing board has the ultimate oversight authority for any charitable organization. The standards noted here seek to ensure that the volunteer board is active, independent, and free of self-dealing. To meet these standards, the nonprofit will have:

- Board Oversight

- Board Size – Minimum of five voting members

- Board Meetings

- Board Compensation

- Conflict of Interest Policy

- Measuring Effectiveness – The effectiveness of a nonprofit in achieving its mission is of the utmost importance. It’s key that potential donors know that when they give to a nonprofit, their money is going to have an impact. This is why a section of the BBB WGA’s standards require that nonprofits set defined, measurable goals and objectives, put a process in place to evaluate the success and impact of its programming, and report on the nonprofit’s progress. To satisfy the requirements the nonprofit must have the following:

- Effectiveness Policy

- Effectiveness Report

- Finances – While the BBB WGA believes that a nonprofit’s finances only tell part of the story of how they are performing, the finances can identify nonprofits that may be demonstrating poor financial management and/or questionable accounting practices. The finance standards seek to ensure that the nonprofit is financially transparent and spends its funds in accordance with its mission and donor expectations. If the nonprofit has the following they must be provided:

- Program Expenses – at least 65% of total expenses are on program

- Fundraising Expenses – no more than 35% of contributions on fundraising

- Accumulating Funds

- Audit Report

- Audit report if gross income exceeds $1 million

- A review by a certified public accountant is gross income is less than $1 million

- Internally produced financial statements if gross income is less than $250,000

- Accurate Expense Reporting

- Detailed Expense Breakdown

- Budget Plan

There are cases where an organization that does not meet the first three standards under finance may provide evidence to demonstrate that its use of funds is reasonable and complies with the standards we have established – and we consider them accordingly.

- Solicitations and Informational Materials – A fundraising appeal is often the only contact a donor has with a nonprofit and may be the sole impetus for giving. This section of the standards seeks to ensure that a nonprofit’s representations to the public are accurate, complete and respectful. If the nonprofit has the following they must be provided:

- Accurate Materials

- Annual Report

- Website Disclosures

- Donor Privacy

- Cause Marketing Disclosures

- Complaints Records

The BBB WGA also provides a list of charities in alphabetical order. Donors may locate a nonprofit on this list and pull up the charity review published by BBB WGA. The report provides information on the nonprofit, including the finding on each of the 20 standards, including the purpose and programs of the nonprofit, information on governance and staff, fundraising, tax status and financial information.

Finally, the BBB WGA provides “Tips for Donors.” This includes publications to help the donor in its charity donation decisions. While it’s ultimately the donor’s decision, the BBB WGA recommends donors avoid or be extremely cautious when contributing to nondisclosure charities. Charities that do not provide BBB WGA with any of the requested information needed to complete a charity evaluation are called “nondisclosure charities.” While this could be benign, some of these charities could also be hiding something by choosing not to disclose.

For more information, please visit Better Business Bureau Wise Giving Alliance

While nonprofits may feel like someone is always watching with so much exposure to their financial information, watchdog groups, including Charity Navigator, Candid, and the BBB Wise Giving Alliance are working to help donors and nonprofits. Nonprofits should see watchdog organizations as another outlet to provide access to their mission and provide a holistic understanding of the operations of the nonprofit.

© 2023 BDO USA, LLP. All rights reserved. www.bdo.com

CECL for Nonprofits Is Here – Helping You Prepare

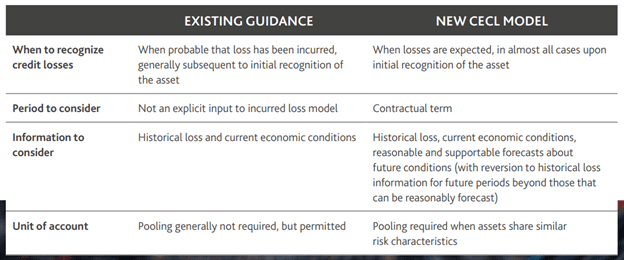

Nonprofits have endured the challenges of adopting several new accounting standards over the last several years. Now, after a lengthy deferral period, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) Accounting Standards Update (ASU) 2016-13, Financial Instruments – Credit Losses (Topic 326): Measurement of Credit Losses on Financial Instruments), commonly referred to as CECL or “Current Expected Credit Losses,” is upon us. Subsequent ASUs were issued related to CECL, which are all codified in the Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) Topic 326.

© 2023 BDO USA, LLP. All rights reserved. www.bdo.com

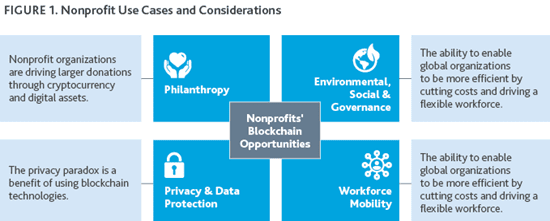

ESG: An Opportunity for Nonprofits

In the for-profit world (and particularly among SEC-regulated companies), environmental, social and governance (ESG) planning has largely focused on compliance and risk mitigation. Given the mission-based orientation of nonprofits, ESG can be approached as an opportunity to grow their mission and impact in a rapidly changing world. The integration of environmental and social sustainability principles into nonprofits’ operational lifecycles will be key to ensuring donor retention and programmatic success for years to come.

The Rise of ESG Standards and Reporting

Over the past few years, multiple global ESG frameworks and standards have emerged to encourage sustainability strategies and provide guidance on sustainability reporting and disclosure. In the for-profit space, ESG reporting is often used to inform investment decisions, comply with regulations and/or give a company a competitive edge. At present, there is no universally followed standard in place, but there is movement toward consolidation of frameworks and standards. The International Sustainability Standards Board (the ISSB) recently merged with the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB). In addition, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) is a leading framework guiding corporate ESG transparency. Together, they are collaborating in an attempt to establish universal metrics for reporting greenhouse gas emissions, human rights protections, diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) progress, and linkages to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

In a few short years, the private sector has evolved beyond the early adopters who have expanded their corporate social responsibility efforts into broader ESG reporting. Today, companies understand the risk of being left behind if they do not adopt comprehensive ESG programming. ESG reporting is becoming the new normal, even for entities not beholden to SEC regulations. In the corporate space, ESG adoption is often a reactive response to the demands of investors, customers and other stakeholders. That said, nonprofit organizations will ultimately face demands from their stakeholders; however they are uniquely positioned to leverage ESG to enhance their mission and brand.

The Social License and Increasing Call for Transparency

Nonprofit organizations exist to serve individuals and communities where gaps in the market are unaddressed by the private sector or government. Their social license to operate comes with the benefit of tax exemption in exchange for providing services and transparency (e.g., IRS Form 990). As the nonprofit industry has evolved, so have reporting expectations. In addition to reporting to the IRS, nonprofits self-report an ever-increasing amount of impact and operational data to third-party evaluators such as Charity Navigator, GuideStar and Candid. ESG reporting is the next evolution of transparency reporting for nonprofits.

As nonprofit organizations are adept at reporting financials and an increasing amount of impact data, they must now navigate the evolving expectations related to ESG stakeholders. For stakeholders focused on the bottom line of mission impact, it must not come at the expense of unaddressed (or uncalculated) negative environmental impacts. For example, stakeholders expect nonprofits to understand their environmental footprint and develop strategies to mitigate it. BDO’s Nonprofit Benchmarking Report shows that 18% of nonprofits surveyed report evaluating their vendors, partners and/or funders for their alignment to ESG policies and actions. If that expectation has not been set for an organization today, it is only a matter of time before corporate donors or other stakeholders will expect to see disclosure and alignment. Donors who are accustomed to evaluating their own investments utilizing ESG indexes will be asking questions about the investment portfolios for endowments that fund a nonprofit organization’s programs. Foundations are increasingly aligning their endowments to ESG metrics utilizing the Global Impact Investing Network’s (GIIN) IRIS+ for measuring, managing, and optimizing their impact. Lastly, stakeholders who expect an organization to embody expectations of DEI will also expect reporting on established metrics that demonstrate evidence of progress.

An Opportunity to Grow the Mission

As nonprofit executives examine the industry landscape and their organization’s opportunity to thrive in the future, sustainability must become a key focus in all aspects of management. From attuning to evolving stakeholder priorities to ensuring continued access to donations and capital, and amplifying the impact of their mission, the integration of ESG principles into all facets of the nonprofit lifecycle will contribute to continued success. Indeed, leading industry organizations such as the American Red Cross have exhibited this imperative by incorporating formal ESG programs into their strategic plans.

Establishing ESG expectations at the leadership level can also drive adoption throughout the organization. Program staff can seize the opportunity to further integrate ESG elements and frameworks into program design, delivery and measurement. Development professionals can utilize ESG reporting to articulate insights attractive to individual, corporate and foundation donors. Communication and marketing professionals can tell a truly holistic story of impact. Finance leaders can ensure that their investments reinforce the organization’s mission.

Written by Karen Baum and Corey Eide. © 2023 BDO USA, LLP. All rights reserved. www.bdo.com

Endowment Woes! Navigating The Nuances With Endowments

An endowment is a pool of funds donated or set aside to be preserved over time in order to support an organization’s mission. Nonprofits establish endowments for a variety of reasons, usually as part of their long-term strategic plan. Donors may contribute assets, such as cash and securities, and make pledges for future contributions to a nonprofit for creating an endowment.

While an endowment is a great idea for long-term planning and may provide continuous funding for charitable activities, it comes with some nuances that must be carefully navigated to ensure it is successfully managed and fulfills the intended purpose for the organization.

The main types of endowments are as follows:

| Type | Period | Description |

| Perpetual (donor restricted) | Perpetuity | Principal (corpus) preserved perpetually, while earnings may be expended based on donor stipulations.

|

| Term (donor restricted) | Varies | Principal preserved for a specified period or until the occurrence of an event, specified by the donor. |

| Board designated | Varies | Principal usually retained, while earnings may be expended. Principal may be utilized upon board approval. |

Potential Challenges

Understanding what they are and how to account for endowments

“I received an endowed gift. Now what?” Nonprofits that never had an endowment may not know where to start. Endowments are governed by guiding documents, which may come in various forms such as a trust instrument, other written agreements from the donor or a board resolution. Identifying the right key words in these documents becomes crucial to ensuring that endowments are set up and accounted for correctly. Additionally, recognizing the type of endowment is also important to ensure the appropriate accounting guidance is applied.

Stipulations plus governing laws

Endowment operations are not only governed by the gift instruments but also by state law. Nonprofits may not appropriately prioritize these. The Uniform Prudent Management of Institutional Funds Act (UPMIFA) is a uniform act that provides guidance on investment decisions and endowment expenditures for nonprofit and charitable organizations. Except for Pennsylvania, all states and the District of Columbia have enacted their version of UPMIFA. Pennsylvania has its own endowment law not based on UPMIFA. Nonprofits may not realize that the donor’s stipulations take precedence over UPMIFA, albeit at times the donor stipulations are not explicit enough to override UPMIFA. This can create confusion.

Unclear donor intent

It is not uncommon for donor agreements to be vague when it comes to conveying the intent and purpose of the gift. These documents can be written by various persons who are not accountants, which can create challenges when determining the appropriate financial statement classification and operating mechanics of the endowment.

Managing endowments

Endowment management can be complex and time consuming without proper resources and knowledge. Nonprofits need to track endowment activity in detail, and retain adequate supporting documentation for all gifts and any investment returns. Funds are often commingled in investment pools, which can create allocation challenges for nonprofit accounting teams. Various levels of expertise and strong internal controls are required for effective management.

Donor changes

Over time, donors can submit modifications to their original gift instruments that are not correctly applied on a prospective basis. Nonprofits need to retain support from donors who make modifications to their endowment agreements as a record for any changes made to the accounting and treatment of an endowment from a donor.

Balancing the objectives

Under UPMIFA, applying prudence to the fund to preserve value is the goal, not just retention of the dollar amount of the initial corpus. This is due to the time value of money. A gift of $100 in 1990 is not worth the same today; thus, to preserve the purchasing power of the fund’s principal, prudent investment and spending policies must be applied, while considering the donor’s stipulations for the fund’s use. Funds with deficiencies (where the fund value drops below the corpus) require special considerations related to spending and estimating future recovery. Many of these challenges also apply to a board-designated endowment fund. A board-designated endowment fund is created by a nonprofit organization’s governing board by designating a portion of its net assets without donor restrictions to be invested to provide income for a long but not necessarily specified period. Proper management and investment tracking are also applicable to this type of endowment fund. The board of the organization establishes the purposes for the endowment fund and this should be documented in the board minutes.

Navigating the Challenges

To effectively manage endowments, nonprofits need to be proactive, sophisticated and careful. They must be willing to make the required investment to educate their team and put the right processes and controls in place. Here are some tips to help organizations navigate the challenges discussed above:

- Adopt formal gift acceptance, endowment and investment policies. Policies should clearly address how funds are to be invested, spent and used (purpose).

- Use consistent templates for gift/endowment agreements to standardize the language and avoid misinterpretation. It is important to have personnel from various areas of the organization review and approve these templates including legal, finance, operations and the board.

- When in doubt, clarify intent! Reach out to donors or their representatives, especially for unusual gifts that come into the organization from trusts and bequests.

- Maintain detailed documentation for all gifts. Accurate and detailed recordkeeping is crucial to the success of endowment operations. Documentation should include certain key information on the donor, assets transferred, specified use, spend rate, investment policy and any modifications.

- Monitor endowment assets regularly and compare to donor agreements often.

- At minimum, organizations should analyze investment returns, spending rates and fund balances throughout the year to ensure funds are being managed in accordance with the gift instrument and state law, if applicable.

- Organizations can go back to donors and discuss modifications, if needed. Seek legal advice before any significant changes are considered and obtain written approval from donors.

- Be mindful that the goal is to preserve the overall purchasing power of the endowment over time. Deficient funds should be tracked separately and monitored more frequently. Elevate these to the board or investment committee for review and a plan of action.

- Nonprofits should consider short- and long-term needs when accepting gifts to ensure it is the right strategic decision. Some organizations may need more short-term liquidity to fulfill their mission; thus, it may not be wise to accept endowments that must be maintained in perpetuity and do not generate adequate income for operations. Overly large endowments have been likened to hoarding in the public eye in some cases. Readers of financial statements may not understand how endowments work and see the large balances and question why the entity needs additional resources. Nonprofits may want to consider more flexibility to ensure the immediate needs of the organization are being met. Outside of perpetual endowments, nonprofits can consider term/quasi endowments or include variance power language in their agreements. This will grant the organization some flexibility in redirecting the use of the assets.

- Proper internal controls are imperative to ensure accuracy and completeness of endowment funds. Nonprofit finance personnel should stay abreast of the latest accounting guidance through research and training.

- Before establishing endowments, nonprofits should examine and quantify the costs to manage an endowment, in terms of time and resources. This may be in the form of investment managers, bank charges and other fees, and additional staff time required to reconcile and track activity.

Over the past three years, nonprofits have had to navigate some turbulent times with the disruption of the world’s economic and political environments due to the COVID-19 pandemic, inflation, and political unrest. Endowments and other reserves may be an opportunity for nonprofits to boost liquidity and permanently support their philanthropic goals and survive in an unstable economic climate. Nonprofits should weigh the benefits and costs of establishing and running an endowment. Organizations should also be mindful of the nuances described above and plan how to navigate these. With proper planning and the right resources, nonprofits can avoid improper classification of gifts and financial statement errors when it comes to accounting for endowments. Nonprofits can also lower reputational risk by ensuring compliance with applicable state law and donor stipulations.

Written by Orynthia Wildes. © 2023 BDO USA, LLP. All rights reserved. www.bdo.com

Is that a Lease? A Focus on Nonprofit Lease Considerations under ASC Topic 842

While Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) Topic 842 is applicable to all entities, the adoption of the new leasing standard by nonprofit organizations is bringing into focus some unique considerations that may impact the conclusion of whether a contract actually contains a lease.

What is a Lease?

To set the stage for some of the nonprofit-specific lease considerations to follow, it is important to understand the definition of a lease under Topic 842. A lease is defined as follows: “A contract is or contains a lease if the contract conveys the right to control the use of identified property, plant, or equipment (an identified asset) for a period of time in exchange for consideration.”[1]

Free or Reduced Rent

A nonprofit organization may be given space, equipment or other assets to use free of charge, or be charged below-market rates for these items. For these types of transactions, a nonprofit organization must consider whether to apply ASC Topic 842, Leases, ASC Topic 958-605, Not-for-Profit Entities Revenue Recognition – Contributions, or a combination of both standards. Let’s illustrate these concepts with some specific examples.

Example 1: Free Rent

Company A provides Nonprofit B with the right to use office space free of charge for five years. Company A retains legal title to the office building but allows Nonprofit B to use the space in furtherance of Nonprofit B’s mission. If Company A had rented the space to another entity, Company A would have charged $1,000 per month for the first year of the lease with a 3% annual escalation of rent for each additional year of the five-year term, which is considered to be the market value.

What’s the accounting for that?

On day one of the arrangement, Nonprofit B would record a contribution receivable, and related contribution revenue, for the full amount of rent payments over the five-year period ($63,710), discounted to present value using an appropriate discount rate.

The revenue is donor-restricted due to time and is released from donor restrictions as the contributed asset (the office space) is used each period. On a straight-line basis each reporting period, Nonprofit B reduces the contribution receivable balance and records rent expense representing its use of the office space.

What is the basis for the accounting?

The transaction in this example falls within the scope of contribution accounting under Topic 958-605 but not lease accounting under Topic 842, because Topic 842 requires an exchange of consideration.

In other words, because Nonprofit B does not pay Company A cash (or other assets) for the use of the office space, the transaction falls outside of Topic 842. If the contributed assets are being provided for a specific number of periods (in this example, the period is five years), the contribution revenue (and related receivable) should be recorded in the period received for the market value of the lease payments discounted to present value.[2]

If the arrangement in this example had not specified the period of use, Nonprofit B would have recorded contribution revenue and the related rent expense each reporting period based on the fair value of the space for that period.

Example 2: Below-Market Rent

Company C provides Nonprofit D with the right to use office space for $250 per month for five years. Company C retains legal title to the office building, but allows Nonprofit D to use the space in furtherance of Nonprofit D’s mission. If Company C had rented the space to another entity instead, Company C would have charged $1,000 per month for the first year of the lease with a 3% annual escalation for each additional year of the five-year term, which is considered to be the market value. For purposes of this example, there is no variable lease cost, no non-lease components, no prepaid rent, no initial direct costs, and no lease incentives. We will assume a 3.5% risk-free rate for the calculation of the lease liability. We will also assume Nonprofit D will use 3.5% as the discount rate for the contribution.

What’s the accounting for that?

On the commencement date of the lease, Nonprofit D would record a lease liability equal to the present value of the lease payments totaling $13,550 (rounded) and a right-of-use asset in the same amount. For simplicity purposes, the present value calculations in this example are based on annual rather than monthly payment amounts. The contribution portion of this arrangement is calculated as the difference between the fair market value of rent ($63,710) and lease payments ($15,000) over the lease term totaling $48,710. Nonprofit D should record contribution revenue and a related contribution receivable[3] at present value of $43,870 on the commencement date of the lease.[4] Similar to the first example, the revenue is donor restricted due to time and would be released from donor restrictions as the contributed asset (the office space) is used each period. On a straight-line basis each reporting period, Nonprofit D reduces the contribution receivable balance and records rent expense representing its use of the office space. This example assumes a known fair market value for the rental payments. When such information is not known, organizations need to obtain such information directly from the lessor or find comparable market data for a similar asset with a similar rental term.

What is the basis for the accounting?

The transaction above falls within the scope of both Topic 842 and Topic 958-605. Because ASC 842 defines consideration as cash or other assets exchanged, as well as non-cash consideration (subject to certain exceptions), only the portion of the transaction requiring payment is considered to be a lease within the scope of Topic 842. The fair value of the lease minus the cash payments made represents the contribution revenue and related receivable.[5]

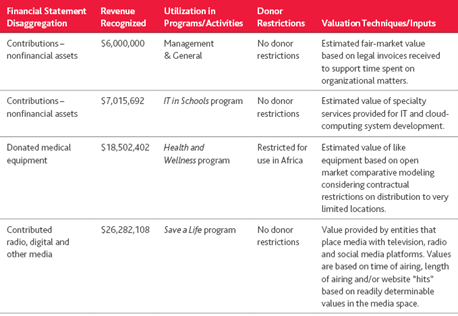

In both of the illustrative examples above, the contribution of free or reduced-rate office space represents a non-financial asset. Nonprofit organizations must consider the revised presentation and disclosure requirements for contributed non-financial assets as outlined in Accounting Standards Update 2020-07, Not-for-Profit Entities (Topic 958): Presentation and Disclosures by Not-for-Profit Entities for Contributed Nonfinancial Assets. This standard is effective for periods beginning after June 15, 2021.

Embedded leases

As nonprofit organizations review their activities and agreements to determine the universe of lease transactions, in both the year of adoption of Topic 842 and in subsequent periods, management should be aware that there may be leases “hiding” within service or other contracts. These types of contracts are referred to as contracts with embedded leases. The following chart provides some examples of service or other contracts where embedded leases may be present:

| Information Technology | Advertising | Inventory Management | Shipment of Goods or Materials | Food Service |

| May contain embedded assets like phones, computers, copies, servers, etc.

|

May contain embedded assets such as the use of a billboard.

|

Third parties may be engaged to assist a non-profit organization with inventory management. Use of warehouse space could be an embedded asset.

|

Use of a rail car or semi-truck.

|

Some organizations provide on-site cafeterias or vending machines. The use of the vending machines, freezers, refrigerators, soft-drink dispensers, etc. could represent an embedded lease. |

As part of internal policies and procedures related to accounting for leases, management should document, in the year of adoption and annually, how the universe of leases was determined, as well as how management considered the possible existence of embedded leases. While embedded leases may not be material to a nonprofit organization’s financial statements, an analysis to determine the relative value of such transactions should be performed nonetheless.

Use of the risk-free rate

As an accounting policy election, Topic 842 permits nonprofit organizations (specifically entities that are not public business entities) to use a risk-free discount rate for leases instead of an incremental borrowing rate, determined using a period comparable with that of the lease term.[6] The use of the risk-free rate may be a more expeditious approach for organizations that do not have a readily available incremental borrowing rate. As a reminder, Topic 842 defines the incremental borrowing rate as “the rate of interest that a lessee would have to pay to borrow on a collateralized basis over a similar term an amount equal to lease payments in a similar economic environment.” If an organization has a real estate lease with lease payments totaling $700,000 over the 10-year lease term, it would not be appropriate for the organization to use its $5 million, one-year, line-of-credit borrowing rate as the incremental borrowing rate because the term and amount of the borrowing is not similar. Organizations wishing to use an incremental borrowing rate that do not have such a rate readily available may need to use external parties such as banks or other lending institutions or valuation professionals to determine an appropriate collateralized rate for certain lease agreements.

In summary, nonprofit organizations should take the time to examine all their agreements to assess whether they have any embedded leases or other arrangements that are subject to lease accounting.

Written by Amy Duffin. © 2023 BDO USA, LLP. All rights reserved. www.bdo.com

[1] See ASC 842-10-15-3.

[2] See ASC 958-605-25-2 and 958-605-55-24.

[3] See ASC 958-605-55-24.

[4] See ASC 958-605-24 and 958-605-25-2.

[5] See ASC 958-605-55-24.

[6] See ASC 842-20-30-3.

Best Practices in Subrecipient Risk Assessments and Monitoring for Federal Grant Recipients

Subrecipient risk assessments and monitoring are critical aspects of federal grants management. These practices ensure that funds are used in accordance with federal regulations, that grant objectives are met and that the risk of fraud, waste and abuse is minimized. The federal government has set forth guidelines in the Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for Federal Awards (Uniform Guidance) found in 2 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 200, which outlines the requirements and responsibilities of grant recipients and their subrecipients. This article will delve into common pitfalls around performing subrecipient risk assessments and monitoring, and the best practices for organizations looking to improve their processes in these areas.

Background

The Uniform Guidance addresses the requirements that subrecipients must comply with in section 2 CFR 200.332. This section describes the required procedures for performing monitoring and risk assessments to evaluate the likelihood of noncompliance, fraud or other issues when selecting subrecipients that could impact the performance and success of the grant.

Effective risk assessments and monitoring are crucial for various reasons, including:

- Compliance with federal regulations: Adhering to 2 CFR 200 requirements is essential to avoid penalties, such as disallowed costs or even suspension or termination of the funding.

- Mitigating risks: Timely identification and addressing risks can reduce the potential for mismanagement, waste or fraud, ensuring that federal funds are used effectively and efficiently.

- Performance and outcome achievement: Proper monitoring helps grant recipients track progress, confirm that milestones are met and determine if adjustments are necessary to achieve desired outcomes.

Common Pitfalls

Below are some of the common pitfalls that plague pass-through entities (prime recipients) that work with subrecipients:

- Inadequate risk assessments: Failing to perform a comprehensive risk assessment prior to executing the subaward agreement or relying solely on historical information may result in an incomplete understanding of a subrecipient’s risk profile.

- Insufficient monitoring: Not allocating enough resources to monitor subrecipients or only relying on self-reporting can leave gaps in understanding that can allow certain risks to go unaddressed.

- Lack of documentation: Inadequate documentation of risk assessments, monitoring activities and communications with subrecipients can hinder an organization’s ability to demonstrate compliance with federal regulations and address potential issues effectively.

- Ineffective communication: Poor communication between grant recipients and subrecipients can lead to misunderstandings, missed deadlines and noncompliance with grant requirements.

Best Practices for Subrecipient Risk Assessments

Below are some of the best practices that we recommend:

- Develop a risk assessment framework: Create a structured process that outlines risk categories, scoring criteria, and the frequency of risk assessments. This framework should consider factors such as prior audit findings, debarment, financial stability and the subrecipient’s experience managing federal funds.

- Conduct pre-award evaluations: Before entering into a subaward agreement, assess the subrecipient’s capacity to manage the grant, considering its technical expertise, financial management systems and internal controls. Performing this required risk assessment in the pre-award phase allows for the determination and inclusion of the monitoring procedures as part of the subaward agreement.

- Implement ongoing risk assessments: Regularly reassess subrecipient risk throughout the grant period to identify any changes in circumstances that may affect its ability to meet grant requirements.

Best Practices for Subrecipient Monitoring

- Develop a monitoring plan: Establish a systematic approach to subrecipient monitoring that includes a schedule, tools and documentation requirements. This plan should consider the risk level of each subrecipient and the nature of the grant activities.

- Provide training and technical assistance: Offer support to subrecipients in the form of training, resources and guidance on federal grant requirements, financial management and performance reporting.

- Conduct regular communication and site visits: Maintain open lines of communication with subrecipients and schedule site visits as deemed appropriate to review progress, verify compliance and address any concerns.

- Review financial and performance reports: Regularly analyze subrecipient financial and performance reports and included data to identify potential issues, ensure compliance with grant terms and track progress toward grant objectives.

- Tailor monitoring efforts to risk level: Allocate resources for monitoring based on the risk profile of the subrecipient, with higher-risk subrecipients receiving more oversight and attention.

- As mentioned above, incorporate monitoring procedures directly into subaward agreements.

Conclusion

Effective subrecipient risk assessment and monitoring are essential for federal grant recipients to ensure compliance with 2 CFR 200, mitigate potential risks and achieve desired outcomes. By implementing best practices and avoiding common pitfalls, organizations can strengthen their grant management processes and ensure the responsible stewardship of federal funds.

Written by Dan Durst and Sly Atayee. © 2023 BDO USA, LLP. All rights reserved. www.bdo.com

Demystifying Nonprofit Cost Allocations

When asked what is at the top of their finance department “to-do” list, many nonprofits name the need for an updated cost allocation plan. An effective cost allocation strategy is essential to organizations’ understanding of how their resources are being deployed. It is also integral to performing cost analyses, such as evaluating funding requirements and comparing actual versus budgeted costs.

Allocations are an efficient and effective way to distribute costs across activities, including programmatic, administrative and fundraising work. However, many find the practical application of allocation concepts challenging to navigate. While some costs are easily assigned to specific activities and do not need to be allocated at all, there are certain costs that need to be proportionately distributed across activities and the organization, magnifying the potential for complexity and errors.

Allocation Methods

When determining an organization’s allocation strategy, limiting the number of different methods utilized can avoid overcomplication, although most organizations use at least two different allocation methods based on the type of cost.

Payroll and related costs are typically a nonprofit’s most significant expense. Organizations determine employee time worked and how that information is documented and substantiated in different ways. However, the goal is ultimately the same: to report these costs in a way that reflects where employees spend their time—that is, where resources are actually being deployed.

For costs other than payroll, or other than personnel service (OTPS) costs, allocation can be accomplished via various methods, including:

- Full-time equivalent (FTE): The FTE method allocates OTPS in the same proportion as employee time worked in different activities.

- Percent of salary dollars: The salary dollars method allocates OTPS in the same proportion as payroll dollars assigned to different activities.

- Square footage (SF): The SF method, typically applied to occupancy costs, allocates costs proportionate to an activity’s share of facility space.

- Per participant: The participant-based method, typically applied to OTPS across programs, allocates costs proportionate to the ratio of participants in each activity.

Allocating Grant Costs

Grant agreements add a layer of complexity to nonprofit cost allocation. Commonly, grants require related costs to adhere to funder-approved, line-item budgets and conform to defined terms and conditions. That is true regardless of whether the funding is from another nonprofit, an individual or a government entity. Adopting and implementing both a consistent organizational cost allocation methodology and a consistent grant allocation methodology is critical. Special attention to grant allocations helps organizations:

- Understand progress against each grant’s budget

- Avoid the risk of double charging (charging the same cost to two different grants)

- Avoid potential consequences of violating such agreements

To provide an example of how an organizational cost allocation methodology interacts with grant allocations, let’s consider the allocation of program supplies expense for a nonprofit with two different grants supporting a certain program:

The nonprofit has chosen to allocate OTPS using the FTE approach. Under this approach:

- The program’s share of personnel time and effort is 20%, so the program also is allocated 20% of shared supply costs.

- The program’s supply expense can be further assigned to the two grants, barring any limitations based on grant budgets and related allowability of those costs per the contracts.

Costs allocated to grants need to be done so with a consistently applied methodology.

From a practical perspective, nonprofit financial systems need to accommodate such multi-dimensional expense tracking. The ability to automate allocation calculations, as opposed to calculating allocations using spreadsheets, is a significant efficiency opportunity. In any case, generating financial reports at different levels of detail, by both activity and grant, directly from the financial system is key.

Once an organization has effectively applied these concepts, the result should be a fair representation of the costs incurred in each program area and in each supportive service. This information is valuable for a variety of reasons. Knowing the cost of programs and the costs covered by grants allows organizations to make more informed choices when evaluating funding opportunities, planning for operational changes and monitoring ongoing activities.

Written by Dan Durst and Gina McDonald. © 2023 BDO USA, LLP. All rights reserved. www.bdo.com

Data Quality for Nonprofits

Data quality is a critical factor for organizations of all sizes, and nonprofits are no exception. Poor data quality can lead to inaccurate business decisions, missed opportunities and even financial losses. Further, poor data quality can impact contributions negatively in several ways. It can obfuscate the nonprofit’s achievements year after year, which can erode donors’ trust or describe fewer accomplishments to its contributors. Poor data quality can lead to marketing campaigns that fail to appeal to first-time donors or are insufficient to recapture previous donors.

Why Data Quality is a Challenge

If data quality is a pervasive issue with real consequences, why have most organizations not solved it? This is the case because assessing and remediating data quality is fraught with challenges, such as:

- Data is an intangible asset and, unlike other assets, does not give detectable signals, such as changing color, giving off smoke or changing smell. In fact, a single erroneous record normally can only be detected when a knowledgeable individual notices the value is not correct in the data.

- It is not cost effective to confirm the accuracy of every data record. It requires real-world observations or corroboration by another source. These are expensive endeavors.

- So much data is collected and processed so quickly now that bad records are not perceived as worth the effort to correct, as they will just be replaced soon.

- Unless the root cause of data quality issues is discovered and resolved, organizations will continue to admit poor data quality into their systems.

Another challenge to data quality is defining what it means for data to be fit for purpose. That definition can change not only across different nonprofits, but within a single nonprofit’s departments as well. In general, high-quality data tends to be defined as:

- A data record presents what is found in reality without distortion (e.g., the ZIP code is the correct ZIP code for a donor).

- The data values follow the correct format (e.g., a U.S.-based ZIP code has five digits with no letters or special characters).

- A data record has no missing values where values are mandatory (e.g., a ZIP code is present for all donor address records).

- There are no duplicate data records for the same entity or event (e.g., the list of valid ZIP codes in a system presents each ZIP code only once per entity).

- There are no contradictions within a data record or across data records (e.g., a ZIP code is the correct ZIP code for the city and state in a donor record).

- The data record represents the most current known information (e.g., the ZIP code in a donor record exists for the donor’s current address, not the prior one).

- The parentage of the record can be traced so that the user knows whence the value was derived (e.g., the donor’s ZIP code was pulled from the contributions database after a donation was made last week).

What Can Be Done

Nonprofits can take one of three stances with regard to data quality:

- Do nothing. Consider poor data quality a cost of doing business and accept the inherent risk.

- Reactive remediation. When data quality problems are discovered—often too late to prevent a damaging business outcome—fix the problem and the class of problems it represents. Over time, data quality will improve.

- Proactive remediation. Pick the data records that are most critical to the nonprofit, usually meaning they are used by more than one department more than once. Define the data quality rules for those data records. Codify those rules into a dashboard that searches for data record violations and aggregates them into a scorecard. When a rule breaks a threshold value —say 15% or more data records have missing values —take action and fix that class of problems.

The proactive remediation approach requires resources and should be taken if the perceived cost of data quality issues is greater than its remediation. In this vein, the approach should not treat all data as equal, but instead consider only the critical data of the entity.

What Questions to Ask

Nonprofits’ leadership should find out what they can about their data quality. Some questions leaders should ask include:

- Is the nonprofit’s data considered trustworthy overall?

- How much time do staff spend cleaning data in preparation for a business analysis exercise?

- No organization has perfect data. Do the managers know where the data quality problems lie? Do they know why the problems occur?

- What steps have the managers taken to detect poor data quality? When found, do the managers fix the data record, fix the problem at the source or both?

The answers to these questions may suggest that leadership devote resources toward not only the assessment and remediation of data quality issues, but in identifying the root cause of those issues and remediating them as well.

Parting Thoughts

Data quality is a critical component of good governance and effective oversight. Nonprofits need accurate and timely information to make informed decisions about their donors and strategy. Poor data quality can distort decision-making, lead to missed opportunities, lower fundraising outcomes and even cause compliance issues. Data quality is also important for risk management, as poor data quality can increase the risk of fraud and cyberattacks and create other business disruptions. Nonprofits should support data quality programs that identify the most critical data records, monitor those records for problems and address problems at the source when they occur.

Written by Jeff Lawton. © 2023 BDO USA, LLP. All rights reserved. www.bdo.com

IRS Drastically Expands Electronic Filing Requirement for 2023 Tax

The Internal Revenue Service finalized regulations on Feb. 23, 2023, significantly expanding mandatory electronic filing of tax and information returns that require almost all returns filed on or after Jan. 1, 2024, to be submitted to the IRS electronically instead of on paper.

Under the new rules, filers of 10 or more returns of any type for a calendar year generally will need to file electronically with the IRS. Previously, electronic filing was required if the filing was more than 250 returns of the same type for a calendar year.

The discussion below focuses primarily on common workplace IRS information forms, such as Form W-2 and 1099 filings and employee benefit plan filings, but the new rules broadly apply to other types of returns.

Insight

Affected employers may need significant lead time to implement new software, policies and procedures to comply with the new rules. Thus, even though electronic filing is not required until 2024 for the 2023 tax year, employers should evaluate what changes may be needed. Simply doing the “same as last year” will not work for many employers.

General Rules

Who is affected? Practically all IRS filers of 10 or more information returns when counting any type, such as Forms W-2, Forms 1099, Affordable Care Act Forms 1094 and 1095 and Form 3921 (for incentive stock options) and other disclosure documents, are impacted by this change this year – that is, for 2023 returns that will be filed in 2024. Even workplace retirement plans may need to file Form 1099-Rs (for benefit payments) and other forms electronically with the IRS starting in 2024 for the 2023 plan or calendar year.

Which returns are affected? In addition to the information returns that are the primary focus of this article, the new rules cover a broad variety of returns, including partnership returns, corporate income tax returns, unrelated business income tax returns, withholding tax returns for U.S.-source income of foreign persons, registration statements, disclosure statements, notifications, actuarial reports and certain excise tax returns.

The rules are not relaxed under these regulations. Thus, returns that are already required to be filed electronically, including partnership returns with more than 100 partners, tax-exempt organization annual returns in the Form 990 series, Form 4720 (for certain excise taxes) and most Forms 5500 (Annual Return/Report of Employee Benefit Plan) continue to be subject to the electronic filing requirement. However, under the new regulations, any taxpayer with 10 or more returns, including income and information returns, must also file its income tax return electronically.

How to count to 10? A significant change introduced by the new regulations is that the 10-return threshold for mandatory electronic filing is determined on the aggregate number of different types of forms and returns. The aggregation rules are confusing because the filings included in the count change depending on which form the determination is made. Also, some filers must be aggregated with all entities within its controlled or affiliated service group to determine if 10 or more returns are being filed for the tax year. For instance, Form 5500 employee benefit plan filers (but not Form 8955-SSA employee benefit plan filers) must count the filings of the employer who is the “plan sponsor” and other entities in the employer’s controlled and affiliated service group.

Example 1: Company A is required to file five Forms 1099-INT (Interest Income) and five Forms 1099-DIV (Dividends and Distributions), for a total of 10 information returns. Because Company A is required to file a total of 10 information returns, Company A must file all of its 2023 Forms 1099-INT and 1099-DIV electronically, as well as any other return(s) that are subject to an electronic filing requirement. The reason for this result is that “specified information returns” such as Forms 1099 and W-2 must be aggregated when counting to determine whether the new 10-or-more threshold for electronic filing is met.